This is the sequel to School Days, an account of my scholastic years. Although I did finish Indiana University in 1969 without a degree, I stayed in Bloomington for the rest of the year, because I wasn’t ready to go home just yet. By staying, I did get an unauthorized trip to New York City with the Singing Hoosiers. I say unauthorized because it wasn’t until after the fact that Mr. Stoll, the chorus director, discovered that I was not enrolled in school at the time. I kept going to rehearsals that following semester, so he had just assumed that I was still a student. I’m sure that I told him, but it must not have registered with him. I think he liked having me around anyway.

By the time the New Year rolled around, I felt that I had overstayed my time there. The University was about to celebrate its Sesquicentennial (150 years) at the end of the month, and the Singing Hoosiers were preparing a special musical presentation for the occasion. I was out of money, out of work, and was not able to pay my rent for February, so I stayed around for the Sesquicentennial, then I headed back to South Bend. I went back to Bloomington in April to attend a friend’s birthday party and when I returned home, after a week’s stopover in Indianapolis, my draft papers were waiting for me. 22 years would pass before I visited Bloomington again.

I actually got drafted a year before I eventually went in. I had received my notice in the spring of ’69, the Selective Service not knowing that my student deferment was still in effect. Upon receiving verification that I was still in school, they left me alone for a year. The next time they contacted me, however, I didn’t have an excuse, so I had to go. But even when I went to Chicago to take my physical, I didn’t think that I would be staying. I expected to be rejected because of my flat feet, or something! No such luck. Before I realized what was happening, I was being sworn in! I went right to a phone and called my mother. ‘Mama, I AM IN THE FUCKING ARMY!’ Friends and acquaintances often ask me about my Army experience. For those of you who did not get to serve in the Armed Forces, you, too, may be curious about what it was like. So in recognition of Veterans’ Day, I will give you some of the highlights (and lowlights) of my military tour-of-duty.

Actually, the Army turned out to be a blessing in disguise. First of all, I spent 16 glorious, though grueling, weeks in sexually-segregated confinement with about 400 virile young men! I couldn’t touch (except for hand-to-hand combat training), but they sure couldn’t stop me from looking! Second, the exercise regimen we were given was the best I have ever had before or since. When I had completed my Basic Training, I was in the best shape I have ever been in my entire life, and I felt better than I have ever felt. Third, just as my mother had supposed, the Army did make a man out of me. I was still an insecure little boy when I got drafted, but by the time I got out 22 months later, I had considerably matured and was now ready to face my future as a responsible young adult. Fourth, during my 18-month assignment in Okinawa, I came to know the nicest bunch of people I have ever spent time with. Most were straight and married, but they were good, loving friends to me. After 54 years, I am still in touch and on good terms with some of them.

In case you are wondering about the gay thing, I should address that issue as well. Although my coming out as a gay man was virtually painless, it did not happen all at once. At the time I was drafted into the Army, I wasn’t exactly out all the way. I was still living “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” I never volunteered the information, and until this time, only one other person had ever questioned my sexual orientation. At Central one day at lunchtime in the school cafeteria, a fellow classmate, Harry Van Scoyk, whom I didn’t even know very well, asked me right out if I were queer. I didn’t even hesitate. I answered, ‘Yes, I am.’ I didn’t see any reason to lie at the time. He didn’t seem disturbed or surprised by my admission. Maybe he already expected as much and is why he asked. You know, like it takes one to know one? I should have inquired why he would ask me such a thing. Maybe he was interested in me that way? He didn’t treat me any differently after that, and I don’t know if he ever told anybody.

So anyway, when I was filling out my military application and came to that certain question inquiring about it, I reluctantly checked the “No” box. I believe that most enlistees/draftees are compelled to lie about that particular question anyway, because of the way it is worded. “Do you have or have ever had homosexual tendencies?” That sure leaves little leeway for a truly negative response. It’s not asking if we actually are practicing homosexuals but whether if we might think about it or have ever considered it. I mean, come on, they’re about to throw us hot and horny young men into a male-segregated environment, so what are we supposed to do? Of course, we have homosexual tendencies! Who doesn’t? As adolescents, even boys that turned out later to be straight probably messed around with their homies or at least thought about it. I know of some myself. The question, or challenge, if you will, is whether we will act upon those tendencies. And even that is open to conjecture. In essence, they are asking us to predict the future. Maybe some guys didn’t have any conscious tendencies, but now that you mention it, they might consider it, when they had not thought about it or ever been tempted before.

If I had it to do over again, however, I would now proudly check the “Yes” box. But at the time, I didn’t know what the ramifications would be if I admitted my faggotry right then and there. Going into the Army was not my intention in the first place, and I had learned that merely admitting that you are gay was not necessarily an automatic deferment. Many draftees during that period declared that they were gay just so they would be rejected. It soon got to their being required to present a note from a doctor or therapist to verify their gayness. So I feared that they might have accepted me anyway, and my being black and queer too, I might have suffered unnecessary persecution, and/or they might have sent me directly to Vietnam to be sacrificed. You know, get rid of two dispensables with one mortar shell. Hey, I’m young and naïvely paranoid! What do I know?

I since have learned that this imagined concern of mine at the time was not completely unfounded. Even though the general attitude is that the Powers-That-Be don’t want homosexuals serving in the military and they will attempt to ban them and discharge them whenever they can, they seem to relax this policy during times of war. It has been reported that when American troops were required to fight in Afghanistan and Iraq, suddenly it’s okay for known gay soldiers to serve. Gay discharges then are greatly decreased, and they were even recruited for combat positions. They need the bodies over there, and if any of them happen to get killed in the process, then so be it. That’s a rather cynical assessment, perhaps, but not entirely unjustified.

So anyhow, I played it safe and allowed myself to be drafted. I was inducted on May 12, 1970 in Chicago. Traveling by bus, I did my 8 weeks of Basic Training in Fort Campbell, Kentucky/Tennessee (the military reservation is situated across both states), where I learned about obedience, discipline, tradition and communalism. I didn’t know how I would fare in boot camp, but I kept reminding myself that if my friend Leo did it, I should be able to do it as well.

I was assigned to Company D of the First Training Brigade of the First Battalion (or D-1-1), which was divided into four platoons (squads or sections), and since we were arranged alphabetically by our last names, I ended up in the 4th Platoon, which was our barracks as well. There were 60 of us in our platoon, from Herman Sands to Dennis Zoran. The whole company, that is, the four platoons, all trained together; we just slept in separate quarters.

When we arrived there, we had to send all our clothes and personal belongings home and were told that whatever we needed from here on out, Uncle Sam would provide it for us. And “he” did, too. Even my eyeglasses were Army-issue. Every hour of our day was planned and accounted for. There was no privacy whatsoever–we even had to take communal dumps, as there were no partitions separating the commodes–and our drill sergeants had to know where each of us was at all times.

Because of the initial trauma I felt when I began Basic Training, I just wanted to maintain a low profile and not draw too much attention to myself. Well, it didn’t happen. I mean, is it my magnetic, outstanding personality, or what? By the end of the first day at Fort Campbell, all my drill sergeants knew who I was by name. The first time I heard my name yelled out, “Townsend!” I thought, Oh, Lord, I’ve been discovered already! So much for desired anonymity.

I didn’t like the exercise so much while we were doing it, but I loved the result when it was all over. We had to get up every morning at 0400 hours (that’s 4 AM!), get dressed in all that heavy gear, go outside and run the mile around the field, in the dark! Then we’d go and have breakfast. After breakfast we’d go back and “clean” the barracks before beginning our training schedule for the day. But how dirty could it be, since we cleaned it just before we went to bed and spent so little time there as it was—that is, just to sleep?

I am normally a late-night person, but when they called “Lights out!” at 1900 hours (7 PM), I was ready to crash, having been on the go the whole day. This being late spring, it wasn’t even dark yet at 7:00. But isn’t that 9 hours of sleep instead the usual eight, you may ask? Well, at some point during the night we had to take turns putting in one hour of night watchman/guard duty, which consisted basically of patrolling the area around the barracks. Of course, nothing ever happened. What did they expect? It was just another pointless chore detail with which to burden us. My turn came around, I think, only once.

I have another barracks memory that I’d like to share. My favorite tenor, other than Mario Lanza, happens to be Karen Carpenter. The very first time I laid ears on her was during Basic Training. I was allowed to retain my portable radio/cassette player/recorder (plus my camera) that I bought while I was at college. The unit was sort of a precursor to the “boom box”—this was the days before Walkmans. Even then I liked to go to sleep with soft music on, and although I didn’t have headphones to listen privately, my barracks mates did not seem to mind.

So this one evening as we were all retiring at bedtime, I had on the local pop station, and they were playing a song that caught my attention, although I didn’t recognize the singer. The song was “They Long to Be Close to You,” and being a longtime Burt Bacharach fan, I had known the song from years before. But I was intrigued by this great, new arrangement and that haunting, sultry voice! I was wondering, Who is that?! When the record ended, the announcer said that it was The Carpenters. Who? I had never heard of them before. Of course, the record became a mega hit and I became a major Carpenters fan from then on. I have everything that they ever recorded. I was devastated and really angry when Karen starved herself to death. How dare she be dead! It has been conjectured that if Karen Carpenter had eaten the sandwich that Mama Cass Elliott allegedly choked on, they’d both probably would be alive today!

I rather enjoyed being outdoors for much of the time, the hiking and daily trips to the rifle range. We made this fun by singing as we marched along. Being the creative musician that I am, I would harmonize and embellish the basic chants, prompting some of the other guys to do the same. Some days we were really cooking, and the drill sergeants didn’t seem to mind. Besides, it helped pass the time.

I barely made Marksman, by the way, which was the lowest shooting grade. It didn’t matter to me, though, because I hadn’t planned on shooting anybody anyway. But if I had not passed, I would have had to do the whole cycle over again. I couldn’t throw worth a damn either. The day I had to toss a live hand grenade, everybody ran for cover, trainees and DIs alike!

Our motto was “Hurry up and wait.” They made us run everywhere (they called it “double time“), and then when we got there, we usually had to wait around to do something. In addition to waiting in line for all our meals and sitting through those tedious lecture classes that I had to endure almost every day, I didn’t much care for the Low Crawl and the “Smoker” either, hateful exercises that we were made to do for our daily routine. We had to crawl on our bellies along the ground like some damned alligator. This was put into practical application one day when we were required to maneuver ourselves under close-to-the-ground-placed barbed wire while live artillery was being fired over our heads. It was the day after a heavy rain, so the ground was still wet with mud puddles. # Hated it! #

The Smoker is where you lie flat on your back and hold both your feet together about five inches off the ground…indefinitely! You think it sounds simple? You try it. The drill sergeants used to threaten us with that one. “Trainee, if you don’t get your shit together, I’m going to smoke your ass!” Or, “Private, get down and give me twenty!” meaning pushups. I was once ordered to squat down and waddle around the post like a duck!

All these calisthenics were implemented as penalties, but they were actually just part of our “PT” (physical training) exercise program. While we thought we were being punished when ordered to do pushups and the Smoker and such, they were, of course, really getting us into fabulous shape. We wouldn’t do that shit voluntarily, unless they made us.

I also did not enjoy the day when we were forced to experience tear gas first-hand. We were ushered into these training area huts in groups, wearing our gas masks. They released the tear gas, then told us to remove our masks. Trainees hurriedly fled. That stuff is vile, y’all! It causes hacking and coughing and it certainly does make your eyes water.

There is a scene in the film Papillon (1973) where the stars Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman, prisoners on Devil’s Island, are eating a meal out of their mess kits, and it is pouring rain into their mashed potatoes and everything. I can really relate to that scene, because I experienced that very same thing! On the days that we had to go out to the rifle range, it was too far to go all the way back to the post for lunch, so food was brought out there to us. One day it was pouring rain right during lunchtime, and since there was no shelter out there on the range, we had to sit there under our ponchos and eat our meal with the rain drenching our mashed potatoes! But that was a prison in the movie, and this was the Army! Hmm. There seems to be a connection.

We all had to serve on KP (kitchen police) duty at some point during the training cycle, and my turn came up only once. But even then, I lucked out. I remember having to work only breakfast instead of the whole day, because it was an important training day that I wasn’t allowed to miss, I was told. I was excused from normal activities another time, when I volunteered to give blood and was given the day off to rest.

Another day that I got out of training was when I went on “sick call.” I wasn’t really sick, it’s just that my periodic tendonitis, or “painful heel” condition prevented me from walking out to the rifle range that day. Since it was such a gorgeous day and there was nobody watching over me, I went out alone to an open, green field near the barracks area and lay down on the grass and just relaxed and napped for several hours. That was a wonderful break in the routine.

I thought that I would enjoy camping out, but the night on bivouac was one of the worst I ever spent. I had to share this tiny tent (which we pitched ourselves) with another guy, and I couldn’t sleep because the ground was cold and I felt bugs and creepy crawlies on me all night, imagined or not. # Hated it! #

We also played War Games earlier that night, which, I guessed, or hoped anyway, was the closest that I would ever come to an actual combat situation, simulated as it was. We had blank ammunition, so we could shoot at each other without anyone getting hurt. That was actually kinda fun—the ambushing and running for cover. It was sort of like Hide ‘n’ Seek with rifles! Bivouac was originally supposed to be for three days and nights, but they had gotten behind in the schedule somehow, so we had to do it only that one day. I am so glad about that. One night out there in the wild was quite enough, thank you!

The drill instructors were a trip unto themselves. They really did a number on us trainees, instilling fear and intimidation on these impressionable youngsters. They always yelled at us and were verbally abusive, calling us meatheads and worthless pieces of shit and stuff. The abuse was always verbal, however, as they never laid a hand on any of us. They “punished” us by making us do those strenuous exercises, which, as I said, were really for our own good.

The Pat Conroy novel, The Lords of Discipline, is set at a military college in Charleston, South Carolina and relates how life is in that situation. Having attended The Citadel himself, I expect Conroy’s story is at least semiautobiographical. In their attempt to make “men” out of their young students, the “cadre” (upperclassmen) do everything they can to break their “plebes” (freshmen cadets) to get them to leave, using tactics of extreme cruelty, violence and humiliation, or else to prove that they have the strength and determination to stay. We didn’t have the option in our case. If any of our trainees were not able to cut it for any reason, that was just too bad. We could not leave but had to stay and endure it. In the book, the cadre would find out each plebe’s dire fears and use it against them. That ploy would not have worked on me, as I did not then and still don’t have any fears or phobias. I am not afraid of anything, not even death.

My fellow trainees were very much afraid of Sgt. Murdock and Sgt. Ratleff, although the day we were on a group training mission together, I got to know Sgt. Murdock and found him to be a real nice, funny guy, not at all like the way he came on to us in public. That’s when I realized that his brusque demeanor was all an act, just for our benefit. They all were actors just playing a role, no different than Louis Gossett Jr. in An Officer and a Gentleman (1982). Late actor R. Lee Ermey was a former Marine Corps drill instructor who went on actually to portray hard-edged military-man roles. I am sure that he got paid a whole lot more as a working actor than he did as an enlisted man, doing exactly the same thing. Our Sgt. Eberly came off less-threatening. He was kind of a gruff, Rod Steiger type.

Sgt. DiGesualdo, on the other hand, was mean-spirited and seemed to be angry all the time, unless that was an act, too. He was always on my case about something, screaming at me and spouting insults, until finally I had to say something to him. I guess he caught me on a bad day, or something. It was at lunch. DiGesualdo was heckling me all through my meal. I don’t even remember now what he was saying—just stupid bullshit. I had had enough of his harassment, so when I had finished eating, I walked over to the table where all the drill instructors ate together and told this bullying SOB to get off my back. ‘Look, Sergeant, I am sick of your petty needling. I do everything that I am supposed to do here and I haven’t done anything to you. I didn’t ask to be here, I don’t want to be here, and you’re not making it any easier for me. Please, just let me get through this and leave me the hell alone!’ Then I walked away, leaving him and the others sitting there with their mouths agape. I guess they couldn’t believe that I actually dared to stand up to my superior like that. But, you know? That was the last time that DI ever messed with me. I guess he said, “Ooh, I am scared of you!” Maybe the sarge was merely testing me with all that harassment to see how much I would take before I finally spoke up. I have found in my life that people will get away with what you let them get away with. If you don’t like the way you are being treated, then just don’t stand for it.

I frequently would fall asleep during those tedious lecture classes. One time the DI called me out. “Townsend, are we keeping you awake?” I replied, ‘Apparently not, Drill Sergeant.” One morning it took me longer than usual to get it together, and I was late falling out for formation. When I got to my place in line, the DI in charge said, “Well, Townsend, I’m glad you could make it!” I quipped, ‘Why, I wouldn’t miss this for the world, Drill Sergeant.’ Do you think I may have had a slight problem with authority?

By the way, I should mention that in the movies that are set in Basic Training scenarios, we always hear the trainees addressing their DIs as “Sir.” That is not the case at all. They would not allow us to call them “Sir.” We had to address them all as “Drill Sergeants.” “Sir” was reserved only for the commissioned officers.

Our company commander, Capt. Dille, was the same age as I was, 22, and we had two “louies” (2nd Lieutenants) who were even younger (they probably were right out of military school), and I had a hard time showing the proper respect I was supposed to afford those particular officers. Why should I call a boy, who is younger than I am, “Sir,” just because he has a couple of bars on his uniform? They should be calling me “Sir”! At least these kids didn’t give us the grief that we got from the drill sergeants, although they liked to strut around the company barking orders at us. I guess it made them feel important. I, however, was not impressed. There were only two other trainees in our whole company in the same situation as I. That is, we all had had four years of college prior to being drafted, so we were the same age. It made us feel a little old, being surrounded by mostly teenagers.

We got one movie night during the cycle when they showed us Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). For the only one-day pass I was granted one weekend, I took a bus to nearby Clarksville, Tennessee. I decided to go alone, in case I found somebody to hook up with, and I didn’t want my Army buddies tagging along to cramp my style, you see. It was a Saturday night, but there wasn’t shit going on there! I had to wear my Army duds, as I didn’t have any “civvies,” making it obvious what I was and where I was from. I ended up at the local USO in town (United Service Organizations—a recreational facility for military personnel), which was also boring, so I didn’t stay there long. The trip there turned out to be a waste of time, but anything to get away from the post, if only for a little while.

After we finished Basic Training on July 10, we immediately had to do 8 more weeks of AIT (Advanced Individual Training). I was assigned to MP (Military Police) School in Fort Gordon, Georgia, located just southwest of Augusta. We were transported there by bus. Keep in mind that this was July and August at a place built on a Southern desert. I can honestly say that this was the most physical labor I’ve ever had to do in my entire life. They always had something for us to do there. When we were not doing our regular training, there was always work for us around the barracks and on post somewhere.

The terrain around our barracks was all sand, and the ground directly in front was always smoothly raked. This is where we fell out for formations, which, of course, always messed up the smoothly-raked sand. No matter. Just as soon as formation was over, somebody would be assigned to smooth it all out again, until the next time we had formation and we’d mess it all up again! They must have sat around thinking up bullshit chores for us to do. One day they made us take shovels and move a pile of sand from here to there! It reminds me of those prison rock pile details, which are also pointless.

There were classrooms to clean up after we had used them and always something in the barracks to do. I had to run the buffer machine in the day room a couple of times, which I did not mind at all. The floors were linoleum. I even worked in the main office as a clerk-typist for a while, which I actually liked. There was one 24-hour job, done in shifts, that we all had to partake at some point during the cycle, and that was CQ (Charge of Quarters) duty. Someone always had to be in the office to answer the phone, receive visitors, generally to be in charge of the post. CQ was a concession in every company that I happened to be in.

There were some good times, too. The day we got to drive the Jeeps was the most fun. We were out on these sand dunes, chasing each other up and down those hills. Cars were jumping and spinning around. It was like driving through deep snow. Dodg’em-on-the-Dunes. We had a blast that day. Another time was the week that we spent in “MP City.” This place was like a Hollywood movie back lot, with streets, fake storefronts and saloons, the whole bit. There we got to practice police procedures, like making arrests and riot control. It really was like an acting class, doing improvs. The “director” would give us a situation and we would “play the scene.” They were giving me personal, professional training and were not even aware of it.

My next one-day pass allowed me to visit nearby Augusta, but there wasn’t a whole lot going on there either. I did get to see, for the first time, the film version of one of my favorite plays, The Boys in the Band (1970), at their local theater, which was worth the trip in itself. Also that day I bought a “civilian” outfit (shirt and pants), so that I would not have to wear my military garb all the time.

I graduated from MP School on September 4th, was home in time for my birthday, and was granted three weeks’ leave—during which time I spent in South Bend and NYC (to visit friends)—before being assigned overseas duty in Okinawa. My mother was pregnant with my little brother, Aaron—in fact, she was due any day—and I was hoping that she would drop the kid before I had to leave for Oakland on the 28th. Otherwise, he would be a year-and-a-half when I got to see him for the first time—which is exactly what happened! I flew out to California (First Class!) on a Monday and Mother gave birth the following Friday, the same day I got my flight to Okinawa.

The flight from Oakland took 18 hours, and that’s entirely over water! Is the Pacific Ocean some big shit, or what?! For those of you not familiar with the imaginary International Date Line, it runs along the middle of the Ocean to adjust the global time zones and runs vertically for the most part, but for some reason makes a zigzag detour around Kiribati, Phoenix Islands and the Line Islands. When you cross the Line going west, you skip a whole day, but you gain a day coming back this way. So going over, having left on a Friday evening, we missed Saturday entirely, arriving there on Sunday morning. But when I returned to the States, I left the island on Friday around 2100 hours (9 PM) and arrived in San Francisco at 1500 (3 PM) that same day, but 18 hours later! That was the longest day I had ever spent at that time (48 hours long). I got to do that again years later, when I experienced the same Monday twice, but I was on a cruise ship this time instead of an airplane, so it didn’t feel the same way. Doesn’t that seem kind of silly that they even do that?

Okinawa is the largest of a 143-member archipelago in the East China Sea area of the Pacific called the Ryukyu Islands (aka the Luchu Islands). They lie due south of Japan and just northeast of Taiwan. The American Armed Forces took over the islands at the end of World War II and eventually gave them back to the Japanese in 1972, not too long after I left, in fact.

There were flights to there that whole week that I was detained in Oakland, but by the time I arrived on the island (October 4), the MP Detachment Company had filled its quota, so the subsequent excess, of which I was a part, were sent to other venues around the island. Now that we were there, they had to find something for us to do. I was assigned to a missile site at Chinen to serve as a security gate guard. This I did for only about 3 months, although it seemed like much longer. Time did not pass so fast over there, it seemed.

Chinen is a peninsula, and the site was situated at the end of the road leading to it–a cul-de-sac, if you will. The only way out was to turn around and go back the same way you came in. It was not long when I realized that I didn’t want to spend the next year-and-a-half opening and closing a fucking gate for 8 hours every day! Talk about your mindless labor! It wasn’t even real work. We didn’t get many visitors to the site on a daily basis, so my duties were only occasional as it was. The island Brass (officers) rarely dropped by, and the place was off-limits to non-military personnel. So on most days during my shift, I didn’t have to do anything. There were a few advantages, however. At the post I had my own private room for a time, I had a lot of time to read, and I had a radio in my guard shack. Being stoned on marijuana a lot of the time certainly helped, too.

(# There’s gotta be something better than this… #)

Eventually, it came to my attention that there was an Army Band operating on the island. So right after New Year’s and with oboe and clarinet in hand (I just happened to have brought them both with me, in a double case that accommodated both instruments), I found the company, which was based in Sukiran, the main Army base on the island (it was more centrally-located, too), successfully auditioned and was reassigned to the 29th Army Band, just in time to help them move into newly-acquired living quarters. At least now I was with other musicians and was playing and singing regularly, having by this time also joined the local Chapel Choir and the Choral Society, which were made up of servicemen and civilians, officers and their wives.

Our luggage was in the form of an Army-issued, olive-drab green duffel bag, in which we transported all our belongings and clothing items. When we first arrived on the island and while waiting to be assigned somewhere, we were lodged in a barracks holding area with no lockers or security for our personal property. So our stuff was pretty much up for the taking, if we didn’t stay right there and watch it at all times. I was out and about exploring during the day, so I was not there on guard the whole time. I wasn’t going to lug the thing around with me. On the very first day that I arrived, somebody stole my beloved radio/cassette player. I imagine that the thief kept it for himself, as there was no pawnshop around at which to hock it. They did, however, let me retain my musical instruments, typewriter and camera, thankfully, all of which I used often during my stay.

There was a lot of idle time in the Band. Most of it was spent hanging around the barracks playing Hearts, our card game of choice at the time. But we did rehearse (not every day) and got to perform occasionally for company retreats and played concerts for the leper colonies on the neighboring islands of Miyago, Motobu and Tokashiki, to which we traveled by helicopter. Some band members were there only to get out of more serious Army detail elsewhere, but a few of us were real, serious-minded musicians. Some of us would get together in our spare time and play duets and trios and such. Richard Balzer played flute and Dick Ingersoll was a top-rate clarinetist. I had my biggest solo moment when I played the Haydn Oboe Concerto (accompanied on piano by Bob Howell from the Band) before a large audience for the annual Ryukyu Music Festival.

Some of my other hangout buddies included Bill Kreutzer, percussionist, and Conrad “Flip” Oller played trombone. Conrad’s father was a “lifer” (an Army career sergeant), who was stationed right there on the island with us. Another trombonist, Mike Hatmaker, constantly had to endure, upon meeting him the first time, people’s singing of # Hatmaker, Hatmaker, make me a hat… # apparently not caring that he had probably heard it before. Of course, I did it, too, when I met him. It was Hatmaker who told me what the letters, U.S. ARMY, on our uniforms stood for: “Uncle Sam Ain’t Released Me Yet.” And there was Michael Norman, who played the trumpet.

Before the Band went on separate rations, meaning that we all agreed to be responsible for our own meals, we ate in the Headquarters Company mess hall, which we shared with the several other units. At every meal the other black soldiers would eat together at the same table and would not mix with the white GIs. After all the strides we have made with integration, some blacks still purposely choose to segregate themselves from white people whenever possible. They apparently could not stand me, because I chose to sit and eat with my friends in the Band. There were other blacks in the Band—I wasn’t the only one—but I don’t remember them ever eating in the mess hall. I didn’t know any of those other black guys, so why would I sit with them just because they are black? I wasn’t desperate to make any new friends. I didn’t sit with the white guys that I didn’t know either. Besides, the guys in the Band would discuss music and recordings at meals, things that I was interested in. When I passed the other tables, they’d be talking bullshit and acting silly. Pardon me for being an artistic intellectual.

The “brothers” had this special, carefully choreographed, jive handshake with which they greeted each other. I think that they meant it to be some kind of unity thing. It was quite involved and complicated, but I thought it was silly and stupid, and I refused even to bother learning it. So some of them would try to test me, you know, see if I’m one of the gang. They’d walk up to me and prompt me into doing the hand jive thing with them, and I’d just stand there and look at them like, ‘Excuse me? What is that?’ Of course, this helped confirm what they already thought about me, that I was “uppity” and was trying to deny my blackness or something. So they gave me much attitude because of it. But my being one who doesn’t give in to peer pressure, I could care less what they thought about me. I don’t consider myself all that grand, but why should I forfeit my dignity or do something I don’t want to do just to please or to be accepted by a bunch of transient strangers whom I’ll probably never see again in life? And none of whom I ever have, by the way.

It later turned out that one of the black guys (I don’t even remember his name) who had been giving me a hard time—you know, making snide comments behind my back, greeting me with scowls and scoffs—eventually joined the Band as a trombone player. Now that we had to work together and he got to know me and started to like me, I think that he felt a little guilty about the way he had treated me previously. But I don’t like two-faced people, so we never did get really close. I can forgive what people have done to me, but I don’t forget. Besides, I found him to be quite unattractive. If he had been cute, I probably would have cut him some slack.

Let me tell you about the first time I went to jail. I didn’t do anything criminal, I was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. I was still with the Band at the time. The entire time I was stationed on Okinawa, the island was under constant conflict. The native Okinawans resented the Americans’ occupation and wanted their homeland back, so there was occasional organized protest and rioting in the streets of Koza City (the soldiers’ primary off-post hangout) and other areas, which required the armed forces to maintain 24-hour riot control guard duty. Whenever there was some trouble anywhere, the island would be put on what was called “Condition Green,” which rendered all areas outside military posts off-limits to service personnel.

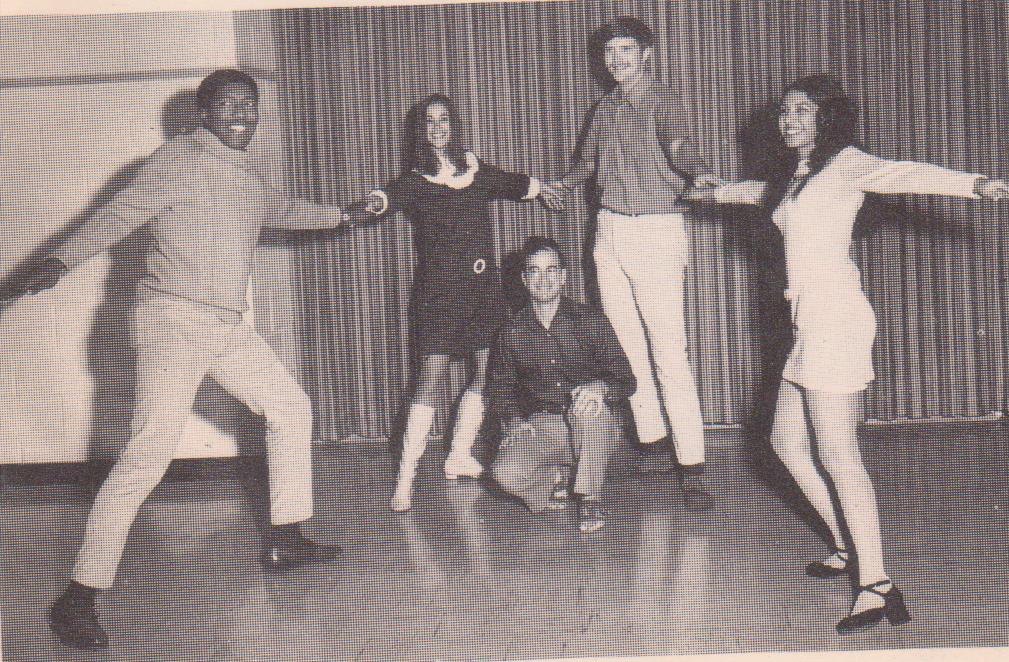

One evening, while the island was on Condition Green, some of my Band buddies were sitting around the barracks playing Hearts, as usual, when somebody got the idea to go out to get something to eat. We had been smoking pot, so we all had a bit of “the munchies,” you see. The four of us (left to right: Conrad, Mike Norman, Me, Bill K.) piled into Bill’s little red car and headed for the A&W Drive Thru, which was only a short distance from our barracks. We had no sooner pulled into the driveway of the place when we were spotted by an MP (whom I did not know) out on motor patrol. He followed us around the restaurant and motioned for us to pull over and stop. We all were then arrested on the spot for being off-post during designated Condition Green and taken to the local stockade.

We were detained there for only a couple of hours, until Mr. Owens, the head of the Band, could come get us released. This first incarceration experience was not too unpleasant. I was with friends, and since we were put in the cell all together, we just continued our party until we were sprung. Unfortunately, I have had four other stints as a jailbird, which were not pleasant, to be sure. Again, I hadn’t committed any crime at neither time. I just seem always to be a victim of circumstance. But that’s at a later time, in another life and in other posts.

I did not get on too well with Mr. Owens. He was a musical idiot, in my opinion, and I had the bad habit of telling him so a little too often, I suppose. So after only about 7 months, he had me transferred to Headquarters Company, also located in Sukiran (so I only had to move to another barracks), where I became the mail clerk, a position I held until I left the island. That was by far my favorite Army job. The hours were few, and I had my own little private office where I could retreat to for several hours a day, as there was no real privacy, to speak of, in the barracks. I would go to the main post office in the morning, pick up my mail, sort it and pass it out to my various units. Then after lunch, I would make another run, and after that batch was sorted and picked up, I was through for the day, sometimes as early as 1500 hours. The rest of the time was my own.

I truly loved it over there. Everything was so inexpensive. Movies cost only a quarter, and a taxicab ride from one end of the island to the other (64 miles) cost only $3.00! I lived in the PX (post exchange, or general store). That just means that I spent a lot of time there. I bought many records and purchased my first real stereo system, with components. Since I did not have the space to store this stereo equipment, I waited until I was ready to leave the island to buy it so that I could ship everything home together. I did have a phonograph in the meantime, I recall, but I don’t remember when and where I acquired it. I loved being able to listen to music at my leisure.

We also had television, but nothing current. All that was available to us were old sitcoms and syndicated fare. I did get a kick watching “I Love Lucy” and “Bewitched” dubbed in Japanese! So I missed out on the new shows that premiered in ’70-’71. New arrivals to the island would be talking about Archie Bunker and Maude, for examples, and I didn’t know who they were. I got to see them all later back home, however, when they aired in syndication.

Even the theatrical movies were several months old by the time they reached the island. There were a number of movie houses spread out all over the island, and they published a monthly schedule of all the movies that were playing. The way it worked was, each new film would play each theater for a couple of days and then move on to another one. So if I missed a movie at the big, main theater in Sukiran, I could catch it later at the Buckner or the one in Koza (the closest three). In this way, I managed to see just about everything that played. I went several times a week sometimes.

We had touring musical artists who came to the island on occasion. There were O.C. Smith, Ike & Tina Turner, both of whom I missed, but I did catch Lou Rawls’ show at the Servicemen’s Club. In the summer of ’71 Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland were on a mission to protest the War, but I missed seeing them, too, because I was otherwise engaged during their rally.

The weather was glorious, too. I spent two Christmases there, and the coldest it ever got while I was there was 60 degrees, at the height of winter in February. The encyclopedia said that Okinawa was typhoon-prone, threatening many each year, but I got to experience nary a one the whole time I was there. We almost had a typhoon once, but it somehow missed us; it never hit our island directly.

It hardly ever rained either, and because of a lack of sufficient rainfall, for several months in 1971 the island suffered a serious drought, which required the residents there to practice enforced water-rationing. Running water was made available to us for only a few hours each day, at which time we could shower and do whatever else, within reason. When it was on, people were not allowed to water their lawns or wash their cars. While it was off, we couldn’t flush our toilets. Even when the water was turned on, it had to be sterilized for a couple of hours before it was fit to drink. I don’t remember bottled water being available to us either. This humbling experience helped me to be more aware of conservation and not to waste water, of all things. As much as I love my water, this was not an easy sacrifice for me. The old adage, “You never miss the water until the well runs dry,” became an apropos reality.

I never have any trouble making friends in new situations, and the Army was no exception. At Fort Campbell two guys in my platoon, Kevin Wieland and Aaron Williams, hooked up with me, and we hung out together all the time, like the Three Musketeers. They both got other assignments after Basic, and I never saw or heard from either one of them again. At Fort Gordon my barracks pals were Bob Hildebrand and Siegfried Tarasenko. Siegfried I lost contact with when we left MP school, but Bob was assigned to Okinawa like me, so we stayed in touch all the while we were there. We used to get stoned together often, and I used to keep him company until his wife came over to join him. I made many new friends in Okinawa. First at the missile site, then the Band and then the Choral Society and Sukiran Choir, which I directed for a while as well as sang in.

How I got into the island’s choral scene was the night I wandered into Sukiran Chapel during a rehearsal of Bach’s Magnificat. I was sitting in the back of the church listening, then when the chorus took a break, this white man came over to where I was sitting and asked me if I sang and if I could read music. I answered ‘yes’ to both questions, and he immediately invited me to join the chorus. That is how I met Jim McGuire and got involved with the Choral Society. See what kind of person he is—so friendly and unprejudiced? I loved how he made no initial assumptions about me.

I actually ended up playing solo oboe in the Magnificat instead of singing in the chorus, and next when I was passed over for the bass solos in the Mozart Requiem, I ended up playing 2nd clarinet in the orchestra. When I helped get my bandmate, Bill Kreutzer, the job of conducting the Choral Society, I then got to do more solo work, and before I left the island, I got to work on Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar with them.

Jim McGuire and his charming wife, Sue, were civilians living and working on the island. Jim and his father owned and operated the Bireley’s (soda pop) bottling plant. Jim and Sue loved to entertain, and their house served as Party Central. Our gang spent many hours at their house for meals, parties and other fun events. One memorable evening was spent at the McGuires’ house constructing snowdrifts out of chicken wire and paper, which were to be used as stage decorations for the Choral Society’s Christmas concert. The chorus also got to appear on a local TV affiliate, doing our holiday program, for which I wrote the script. In addition, our Summer Sounds ’71 concert was recorded live, and we produced an album from it.

Mary Prange and I got to be very close. She was sort of my “girlfriend,” although it was strictly platonic. Mary taught math at the local American high school, but, like me, she was interested in musical theater and drama. The night of the McGuires’ second Christmas party, at which we entertained each other, Mary and I worked up a scene with song duet, “A Fact Can Be a Beautiful Thing” from the musical Promises, Promises, and performed it for the party guests.

Those people fed me to death over there! Almost every night of the week somebody in the choir was inviting me to their house for dinner, and since I did not have my own cooking facilities at home, I always accepted. In addition to eating at people’s homes, the church held a sumptuous pot luck supper once a month, which I always attended, and we were always going out to restaurants for group meals. By the time I left the island, I had blown up to over 200 pounds, at that time, the most I had ever weighed in my life. Blimey, I wish I could get back down to 200 now!

The gang regularly went on Sunday outings, too. We all sang in the post chapel choir together, and after the service and lunch we’d pile into somebody’s cars and visit the island’s tourist spots. There was an old, uninhabited castle, which was made into a zoo. That’s where Mary was kissed by an old camel! There was Suicide Cliff, where, when they surrendered in 1945, the Japanese troops all plunged to their deaths. More about that later. There was an Aquarium up north, and in Naha, the capital, is located the famous geisha palace, Teahouse of the August Moon, which was off-limits to military personnel, so I never got to see the inside. There is a 1956 film with the same name about the place, which stars Marlon Brando and Glenn Ford.

I once went to a movie theater in Naha and saw Love Story (1970), for the first time, in English with Japanese subtitles! The Okinawan natives held an annual island-wide Tug-o’-War in one of the villages, which I witnessed one Sunday afternoon, and I took pictures of the event and of the humongous rope that they use in the ritual. One of the nearby islands is Iwo Jima, where that famous photograph cum statue of those Marines raising the U.S. Flag took place. The McGuires also had a yacht in which a group of us sailed to Admirals Island one afternoon for a picnic and exploratory hike.

I had heard that there is a high incidence of longevity among the Okinawan natives. I have since learned that over 900 residents of the islands are over age 100! Scientists have not yet discovered their secret to super longevity, but it may have something to do with their easy-going lifestyle, or ikigai, “a reason to get up in the morning.” I noticed how everybody was so laid back over there, no one in a hurry or rushing around, like it tends to be in the big cities. I recall that my uncle Lester was always quiet and easy-going and he lived to be 111! Consider that tortoises live for a very long time, too. So, maybe taking it slow and easy is the key.

I considered staying there myself after my Army stint, maybe getting a job teaching at the high school. But it didn’t work out. I had to separate stateside and I just couldn’t see making that 18-hour trip two more times. Besides, the island’s subsequent reversion most likely changed things there, I‘m sure.

I suppose that inquiring minds, if you’re like me, may be wondering about the sexual situation in the Army. Since, as everybody knows, there are no homosexuals, besides myself, in the armed forces, right?, you must think that I spent my two years being celibate. Hah! Think again. Actually, there are as many queers in the service as there are anywhere else, and don’t let anybody tell you otherwise. Although I did not do anything during Basic Training or MP School, I was quite sexually-active while I was in Okinawa. As it so happened, I don’t remember being horny at all the whole time I was at Forts Campbell and Gordon, even though I was around all those fine, humpy, young men all day long. There was an ongoing rumor that saltpeter, a nitrate (nitrite?) which supposedly represses one’s sexual libido, was added to the potatoes on a daily basis. If that is true, it must have worked, because I didn’t have the desire even to jerk off. I guess they didn’t trust us, so they chose to suppress any desire we normally would have if left to our own devices.

Anyway, there were indeed queers galore during my Army stint. The trick, though, was finding out who they were, and we gays seem to have a knack for ferreting out others like ourselves. Call it a sixth sense, “gaydar” or whatever, but I, for one, do seem to have the knack. It’s really a game with us, trying to figure out who is gay and who isn’t, and the military closetness really added to the challenge, as you can imagine. When I got to Okinawa, I soon discovered where the gay boys met and hung out, but even with my usual astuteness, I still got occasional surprises. I had guys coming on to me who I never suspected to be gay, although they apparently had my number, or at least suspected.

I had my regulars among the soldiers and even some American civilians, who were either on the island because of their jobs or they were tourists. I never got to fulfill my desire to make it with a native Okinawan man, however, and I never found the reputed local gay bar, if there really was one. I did have plenty of chances to sample the “working girls” there, though, but I repeatedly resisted the opportunity. They were always looking for a “short time” (a cheap quickie) with the servicemen via the bars, nightclubs and massage parlors. I told you that everything was cheap over there, including solicited sex. One could get laid for as little as $5!

When I was still at the missile site, a few of the guys and I went into Koza one night to get us some “poon-tang”—at least, they did. While each of them were upstairs, presumably getting it on with the girls they had picked up at the bar, I just sat at the bar, talking to the remaining girls and waited for my buds to return. Even for appearances’ sake, I wouldn’t bring myself to do something that I really did not want to do, especially if I had to pay for it! I don’t think that any of the guys ever figured out my story. At least if they did, they never confronted me about it.

Bill Kreutzer didn’t come out to me until he had settled in San Francisco and told me in a letter. We used to camp with each other all the time, too, but he would never come right out and admit to me that he was a “friend of Dorothy.” He must have known it about me, because I was pretty much myself by that time. The people who didn’t suspect were all just in denial. I didn’t pretend to be something I wasn’t, but I didn’t volunteer anything either. For appearances’ sake, though, I managed to conceal my homosexuality right along with the other gays in my company.

I did get into a little trouble about five months before my time was up, which started a certain chain of events which lasted until I left the island. When I moved to Headquarters Company after the Band, the bunk area in the barracks in which I lived was divided into sections, or “cubes,” with two bunk beds to a cube. The wall lockers that were assigned to us, in which to keep all of our belongings, were very tall and wide enough so that, when placed side by side, would form a partition on at least two sides. This gave us some degree of privacy, although there were no doors. This particular barracks was not fully-occupied, so all the bunks were not being used. I even had a whole bunk bed to myself, although I did have to share my cube.

It was the very day I was to be promoted from E-2 Private to E-3 PFC (Private First Class). I had been there for about a year by this time. It would have been my first earned promotion, as we are automatically promoted to E-2 status after AIT. The only merit of a military promotion is that it puts you in a higher pay grade. After breakfast and before I had to go to my job, I was called in to see my Commanding Officer, for the purpose of officially receiving my promotion, I thought. Instead, I was informed that it had just been brought to his attention, by someone in my platoon, that I had been observed making out with my cubemate in our bunks at night. I will admit to you here and now that I am guilty as charged (and it certainly was not the first and only time either), but I did not admit it to my CO at the time. And I assure you, it was completely consensual. I never take advantage of anyone against their will and never have. In fact, he was the one who first came on to me!

Again, if I had it to do over again, I would probably confess, and I don’t know why I didn’t then. I suppose it was because I was actually enjoying the Army by this time and I didn’t want to be kicked out with a dishonorable discharge. So I denied the charge, and since it was only my accuser’s word against mine, they never could prove it. I even had to see the company psychiatrist, so that he might ascertain if I were queer or not. But how could he or anyone else ever prove such a thing when all I have to do is give the right answers by telling them what they want to hear? The doctor said something interesting, though. He told me that in itself, being gay was not a crime and something that they couldn’t do anything about. It appeared that he was telling me that it was all right to be gay, and I suspected that he could have been, too. The issue was, did I actually do what I was being accused of? I still denied the charge.

As it takes two to tango, I have always wondered why my friend was not called in as well. Why only me? Or maybe he was, he just didn’t tell me. I was pretty sure who ratted on us, by the way, even though the CO would not tell me who it was. When I ran into the rat fink, John W., later that morning, he had the guiltiest look on his face. Uh-huh, just as I thought. Unbeknownst to me, he probably had caught us one night while we were getting it on. With no doors to close, it was always a risk of being caught in flagrante delicto. We just took our chances. I am surprised that we didn’t get caught more often than we did. A closet case himself, I suspect, but one that I had nothing to do with sexually, John was probably just jealous because I wasn’t giving him any action. I might have, though, if he had made his interest known, indiscriminate whore that I am. And I don’t think it was any coincidence that John was up for promotion, too, that day–maybe it was a quota situation and he thought he would have a better chance if he could eliminate his competition. Why else would he report me like that?

So I did not get my promotion, as it turned out. Due to the short term I was to serve, I wouldn’t have made it beyond E-3 anyway. But now I had to be careful about what I did, at least around the barracks, because if I got caught again, it would only validate the charge against me. I was somewhat hesitant about whether to include this very personal chapter of my Army experience, but hey! I wanted to be honest with you and give you the whole story, judgment be damned. You should hear about the unpleasant parts as well as the good. I cannot change the past, what’s done is done, and the truth needs no justification. Plus, I thought you would like to know how gay issues are dealt with when they arise. As usual, things seem to work out in my favor.

In my case, my superiors had a hard time disciplining me. Since most GIs join the armed forces voluntarily, the ultimate punishment is dismissal. To keep us in line, they could always threaten us with discharge. But since I, as a draftee, didn’t want to be there anyway, they couldn’t use kicking me out as an incentive to make me behave. So with me they used harassment, gave me bullshit details and constantly put me on guard duty. As long as I stayed out of the stockade, I didn’t care what they did to me, although what I knew about the stockade was that it was no different than boot camp, which was much like prison, as I alluded to earlier.

During my mail clerk assignment at Headquarters Company and when it was our turn to be on call for riot control guard duty, one Sunday evening I failed to show up for a company formation at which attendance was taken, and I was penalized with an Article 15 citation for missing it. I don’t remember why I did not attend. I must have been doing something that I deemed to be more important, or I just couldn’t be bothered at the time with such nonsense. Besides, they hardly ever took attendance anyway.

I don’t know the exact wording for it, but an Article 15 is a disciplinary action given for a military infraction. Yes, they could be unreasonably strict when they wanted to be. So I missed a stupid formation! Big-fucking-deal! How is that a crime? Maybe they were being more attentive in my case because of that other business. I suppose that I should have been more cautious myself and expected that Big Brother was watching me more closely now and just waiting for me to slip up in some way, in order to come after me.

My punishment was to sweep and clean the barracks office after duty hours for a designated period of time, which I didn’t mind doing, but Monday evening was my choir rehearsal night. I was directing the Sukiran choir at this time, and there was no way for me to contact everybody to change the rehearsal for another day or time. Communication by phone was non-existent at the time. I could not just fail to show up with no explanation. That’s not right. So I asked my barracks sergeant if I could start my extra detail tomorrow night instead, when I would be free. “Townsend, you will report to this office at 1800 hours tonight!” ‘I can’t come tonight. I have choir rehearsal. People depend on me.’ “You will report to this office tonight!” Why must he be so unreasonable? So, what did I do? I went to my rehearsal. To hell with that guy! Who does he think he is? He can’t tell me what to do!

The next morning I was presented with another Article 15 for violating the first one! I told you that they were strict. My punishment this time was my being put on company restriction, which meant that I was not allowed to leave the barracks for the next two weeks, except for my day job. So I’m grounded? What am I, an unruly child?! And to make sure I honored the restriction, I had to sign in at the office, every hour, on the hour. But I even managed to get around that, at least for the first few days. Tuesday and Wednesday of that week were no problem. I didn’t have anywhere to go and I got a good rest, besides, just relaxing, reading and listening to records. I didn’t even have to do the original custodian detail.

On Thursday evening, however, I had rehearsal for the Choral Society, so this is what I did. The rehearsal started at 7:00. I signed in at 7 then went to rehearsal. At five minutes to 8, I borrowed Mary’s car, drove back to the barracks to sign in for 8:00, then went back to rehearsal. We were finished before 9, so I got back home in time to sign in again. After that first week, it got easier, and they weren’t watching me as closely. I was busted back to E-1, by the way, as the result of those two Articles 15, in addition to the company surveillance.

I am sometimes asked if I was ever worried that I would have to go into actual combat. After all, the war in Vietnam… Excuse me, I almost forgot that war was never declared, was it? The conflict in Vietnam was in full swing, but I had no intention whatsoever of going there or fighting anybody. That just was not in the cards for me. They couldn’t make me fight; I would have simply refused. (“Hell, no! I won’t go!”) You know from some of my other posts how antiwar I am and that I am a committed pacifist. The Army may be a lot of things, but it does try to be fair and sensible, in some respects. Infantry assignments are mostly reserved for gung-ho volunteers, enlistees, high school dropouts, those guys deemed relatively-disposable, who apparently don’t mind dying for their country, or else they wouldn’t have volunteered.

We all were given extensive evaluation tests when we first went in, and with all my education and special skills, they probably realized that I would be more use to them alive than dead. They even tried to get me to sign up for officers’ training school, but I declined. I didn’t want to make any long-term or special commitments. Let me serve my two years and get the hell out of here! I do regret, however, not accepting the Airborne training assignment when it was offered to me. I would have gotten to be a paratrooper, which I have always wanted to do, but at the time I was so tired from the constant work and believed Airborne would be even more harrowing and strenuous. So I turned it down, too.

The Army recruiters managed to entice many of my college friends into enlisting for four years after graduation instead of risking being drafted, convincing them that they could pick their assignment and would not have to be sent to the infantry. Well, they all fell for their line and signed up for four years. Some of them did get cushy assignments after Basic, but it was no guarantee that they would or that they would avoid Vietnam. It never occurred to me to defect to Canada. I decided to take my chances with the draft, and you see that I lucked out. I got good assignments, I had to serve only 22 months in all and I didn’t even have to fight.

Many of the draftees were being granted early outs, and I was put on the list, too. I guess they couldn’t wait to get this willful, incorrigible (alleged) faggot out of their midst. The Choral Society was in rehearsal for Jesus Christ Superstar, in which I was to play Judas, so I didn’t want to leave until after the performance. I even asked for an extension, but it was flatly denied. So they did find an appropriate punishment for me after all! It’s like with the sadist and the masochist. The masochist: “Please, sir, beat me, beat me!” The sadist: “No!” So as soon as my orders were drawn up (in early March), I was out of there, but with an Honorable Discharge, thank you.

People came and went all the time, as their orders dictated. Jim and Sue would use any excuse to have a get-together, so whenever anybody in our family group left the island, they would throw them a Going-Away party. I, being one of their special friends, was, of course, no exception. They threw me a great going-away bash at their house three days before I had to leave. I received presents, cards, a cake, and my friend Carolyn Ryan, who also was over there as a schoolteacher, took the time to write a poem in my honor (it’s really in the form of a roast), which she read aloud to the attending party guests. I am presenting it here for your enjoyment and my evaluation.

AH, MEMORIES! (or Who Has the Goods on Cliff?)

By the shores of Okinawa on the strip of Kadena Base,

One large bird brought forth our Clifford, dropped him off with style and grace.

To the barracks he did saunter with his oboe in his hand;

Yep, you guessed it, he was to play for the 29th Army Band.

Onward to Sukiran Choir came our Clifford singing low;

But we notice, rarely softly, so we did hear that music flow.

Singing, outings, parties, job kept him busy we can guess;

Indeed, his time was taken, but was Cliff ever late? By golly, YES!

Into church he’d creep, plastic bag in hand,

Arriving in the sanctuary just in time to stand.

Oh, he’ll deny that this is true,

But we are witnesses, me and you.

At movies he sits so quietly in his seat,

Just sleeping like a baby. Ain’t he sweet?

Cliff is full of curiosity;

A case in point, we shall see;

Suicide Cliff we did explore;

After a while, Cliff was around no more.

We waited, searched, returned to the car;

Still no Cliff, though we looked very far.

We went back down, now drained of all pep;

Met Cliff coming up, counting each step!

There are more tales that could be told,

But will remain memories until we’re old;

For someday we will gather in his den,

And we will play “Remember When…?”

No, I don’t deny any of what Carolyn said about me. She had me pegged pretty well. I was often late for rehearsals and church services and such. I was young and frivolous in those days. I became much more grounded and responsible later on. I hate being late for anything, so now punctuality is very important to me. I don’t like for people to keep me waiting for them, so I am respectful enough not to make them wait for me. I did use to carry everything in a plastic bag, too. I must have started doing that at college. My pockets were not big enough for my music, my camera, reading material and other personal items. This was before it occurred to me that I could have carried a shoulder bag for that purpose. Yes, there was a time when my voice would stick out in a chorus, before I learned how to blend, and too, I used to doze at the movies. I still do, even at home. But as far as gathering in my den someday, I doubt that will ever happen, even if I, in fact, had a den. I suppose it could occur in someone else’s den, however.

There is a story behind that Suicide Cliff report. It was one Sunday afternoon when the gang went to see that tourist site. Down below the actual jumping-off place were subterranean tunnels where the Japanese soldiers had their headquarters, and there was a dense, wooded area adjacent to the ocean. I love to explore and I admit that I do have a tendency to wander off from groups I am with, and that is what I did that day. While we were exploring the area, I got separated from the others. I went into the midst of the jungle alone and got myself lost. I didn’t know where I was or how to get out, and I was becoming worried because it was getting dark. So out of worry and frustration, I did something that I had never done before or since. I started yelling ‘Help!’ just like in the cartoons and movies. And as luck would have it, some hikers happened along where I was and showed me the way to the main path that led out of the thicket. This path ended with a very long set of concrete stairs that led up to the parking area. Curious about the number of steps there were, I decided to count them as I ascended. Before I got to the top, I spied Carolyn and some of the gang coming down toward me. I don’t remember now exactly how many steps there were, but there were over a hundred.

Looking back and all things considered, I can rightly say that the time I spent on Okinawa was one the happiest periods of my life. Everything didn’t always go my way, as every life has its ups and downs, as I have related to you, but the pros greatly outnumber the cons. I was in a place with perfect weather and an incredible economic situation. After my impoverished college experience, I had learned that I could live comfortably on very little money. And since everything there was so damned inexpensive, I was able to accomplish that. I didn’t have to pay for lodging, and often my meals were free. The only things I spent money on, other than my new stereo system, were records, printed music and movies, plus some souvenirs for myself.

None of my various jobs could be considered hard labor: sitting on my ass most of the day, making music and handling mail. That’s nothing. I mean, I do most of that anyway, even when I‘m not getting paid! I had a great artistic outlet and entertainment opportunities, where I got to sing, dance, play musical instruments, conduct, act, even write. I learned a good bit of Japanese, too, while there, which I can still speak even today. I had fun-filled socializing with dear, loving friends, the food was plentiful and delicious, and I was getting satisfying, enjoyable sex on a regular basis. Come on, what’s not to like?

So I finished out my term and was returned to the States and released on March 4, 1972, two months early, only six weeks before the island reverted back to Japanese rule. If I had it to do over again, that is, if I had known for sure that I would have to serve in the Army, I would have gone in right after high school, instead of the other way around. Because when I was discharged, I was then ready for college. I was now 24 and had matured enough really to buckle down and do some serious studying. I could have taken advantage of the G.I. Bill, too. But because I had already been through that, I just didn’t want to do it all again. Seventeen consecutive years of schooling had been quite enough, thank you.

With my severance pay and accrued leave pay (I didn’t take any of my leave time, so they paid me the money instead) I went back to South Bend and applied for Unemployment Compensation for the first time. So in reflection, even though I didn’t want to go into the Army, I’m certainly glad that I did. It was a series of first-time experiences, some good, some not so good, but then I think about all the wonderful, life-changing adventures and fun things that I would have missed out on if I had not gone in.

Happy Veterans Day, my fellow veterans (and non-)!

[Related articles: “I’m Working Here!”; More Name Dropping; On the Road With Cliff; School Days]